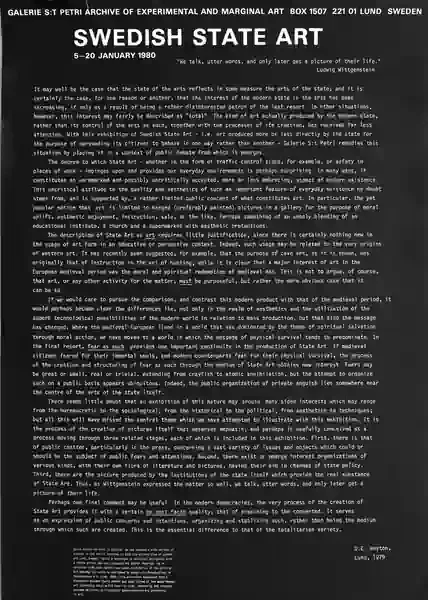

CLICK TO VIEW PRESS RELEASE

SWEDISH STATE ART

5–20 JANUARY 1980

“We talk, utter words, and only later get a picture of their life.”

— Ludwig Wittgenstein

It may well be the case that the state of the arts reflects in some measure the arts of the state; and it is certainly the case, for one reason or another, that the interest of the modern state in the arts has been increasing, if only as a result of being a rather disinterested patron of the last resort. In other situations, however, this interest may fairly be described as “total”. The kind of art actually produced by the modern state, rather than its control of the arts as such, together with the processes of its creation, has received far less attention. With this exhibition of Swedish State Art — i.e. art produced more or less directly by the state for the purpose of persuading its citizens to behave in one way rather than another — Galerie S:t Petri remedies this situation by placing it in a context of public debate from which it emerges.

The degree to which State Art — whether in the form of traffic control signs, for example, or safety in places of work — impinges upon and provides our everyday environments is perhaps surprising. In many ways, it constitutes an unremarked and possibly uncritically accepted, more or less embracing, aspect of modern existence. This uncritical attitude to the quality and aesthetics of such an important feature of everyday existence no doubt stems from, and is supported by, a rather limited public concept of what constitutes art. In particular, the yet popular notion that art is limited to hanged (preferably painted) pictures in a gallery for the purpose of moral uplift, aesthetic enjoyment, instruction, sale, or the like. Perhaps something of an unholy blending of an educational institute, a church and a supermarket with aesthetic pretensions.

The description of State Art as art requires little justification, since there is certainly nothing new in the usage of art form in an educative or persuasive context. Indeed, such usage may be related to the very origins of Western art. It has recently been suggested, for example, that the purpose of cave art, as it is known, was originally that of instruction in the art of hunting; while it is clear that a major interest of art in the European medieval period was the moral and spiritual redemption of medieval man. This is not to argue, of course, that art, or any other activity for the matter, must be purposeful, but rather the more obvious case that it can be so.

If we would care to pursue the comparison, and contrast this modern product with that of the medieval period, it would perhaps become clear the differences lie, not only in the realm of aesthetics and the utilization of the superb technological possibilities of the modern world in relation to mass production, but that also the message has changed. Where the medieval European lived in a world that was dominated by the theme of spiritual salvation through moral action, we have moved to a world in which the message of physical survival tends to predominate. In the final resort, fear as such provides one important continuity in the production of State Art. If medieval citizens feared for their immortal souls, and modern counterparts fear for their physical survival, the process of the creation and structuring of fear as such through the medium of State Art obtains new interest. Fears may be great or small, real or trivial, extending from crayfish to atomic annihilation, but the attempt to organize such on a public basis appears ubiquitous. Indeed, the public organization of private anguish lies somewhere near the centre of the arts of the state itself.

There seems little doubt that an exhibition of this nature may arouse many side interests which may range from the bureaucratic to the sociological, from the historical to the political, from aesthetics to techniques: but all this will have missed the central theme which we have attempted to illustrate with this exhibition. It is the process of the creation of pictures itself that deserves emphasis, and perhaps is usefully conceived as a process moving through three related stages, each of which is included in this exhibition. First, there is that of public chatter, particularly in the press, concerning a vast variety of issues and objects which could or should be the subject of public fears and attentions. Second, there exist or emerge interest organizations of various kinds, with their own flora of literature and pictures, having their aim in changes of state policy. Third, there are the picture produced by the institutions of the state itself which provide the real substance of State Art. Thus, as Wittgenstein expressed the matter so well, we talk, utter words, and only later get a picture of their life.

Perhaps one final comment may be useful. In the modern democracies, the very process of the creation of State Art provides it with a certain ex post facto quality: that of preaching to the converted. It serves as an expression of public concerns and intentions, organizing and stabilizing such, rather than being the medium through which such are created. This is the essential difference to that of the totalitarian variety.

D.E. Weston

Lund, 1979

D.E. Weston was born in England, but has resided in Sweden for several years. He holds academic degrees in the philosophy of science and in the social sciences and has been a university lecturer at Lund since 1966. Language and philosophy have occupied his academic interests, though he has some formal training in the visual arts. For the Galerie S:t Petri exhibition “Swedish State Art”, he has written the essay above, which provides the theoretical framework for the exhibition and forms part of a continuing study of the relationships between communication, art, and the state. Other publications and professional connections are available upon request.