CLICK TO VIEW PRESS RELEASE

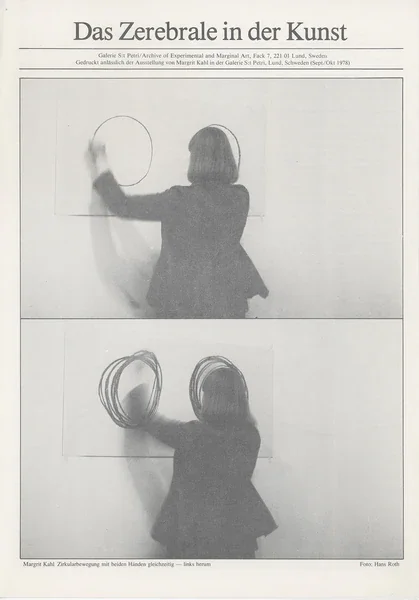

MARGRIT KAHLDAS ZEREBRALE IN DER KUNST29. 09 - 28.10.1978

The Function of the Human Brain and the Compulsion Toward an Analytical State of Consciousness in Advanced Industrial Society —

Reflections on the Avant-Garde of the Visual Arts in the Second Half of the 1970s, Exemplified by the Work of Margrit Kahl

From 1970 to 1975, Margrit Kahl studied sculpture and the theory of artistic work under Franz Erhard Walther at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste in Hamburg, within the framework of an expanded concept of art. In 1975, she co-founded the artist initiative Galerie vor Ort.

Since the early 1970s, she has been experimenting in the field of phenomenologically oriented studies on certain movement experiences of the human body. The central theme of her photographic studies appears highly symptomatic of contemporary art and reflects the consequences of the artistic attitudes of the 1950s and 1960s, which focused on questions of human identity and the ontological issues of modern industrial society.

This raises the question of whether Margrit Kahl’s interest in Merleau-Ponty, Bachelard, Husserl, and Heidegger allows us to conclude that she advocates a form of phenomenologically motivated art.

Her engagement with these philosophers is connected to the question of existence, the notion of autonomy, the problem of form and content, and the question of what constitutes artistic authenticity. Her artistic goal is to grasp human existence in a phenomenal way. In this sense, one could indeed speak of a phenomenologically motivated approach.

That she does not align herself with any particular -ism in her artistic activity is thus understandable. We shall not dwell on terminological distinctions here — but it is precisely against this background that the conception of her work can be clearly distinguished from the aims of Behaviour Art.

When we consider the artistic expressions of many contemporary artists, especially those of the avant-garde, the gap seems to be widening between what could be described as phenomenologically motivated art, in contrast to Behaviour Art. In fact, the two views do overlap. Yet two fundamentally different conceptions can be discerned regarding the position of the human being in his environment:

one, the view that the human being is merely a product of his environment — that is, a more behaviourist or analytical attitude;

the other, the phenomenological attitude, which asserts that the human being shapes society.

There thus exists a fundamental distinction between, for example, dialectical materialism and Freudian interpretation on the one hand, and the standpoint of Kantian philosophy on the other.

In the mid-1970s, several scientists, based on methodological studies, arrived at the conclusion that the two hemispheres of the human brain have different functions: the left side performs a more analytical function, while the right side performs a more synthetic one.

McLuhan (*) reflected on this issue. Without developing a biological theory, he suggested that the hemisphere associated with the more analytical role has, in the course of the progress of communication technologies, evolved cybernetically, while the other hemisphere, less developed in this respect, controls the movements of the opposite side of the body.

If one considers Margrit Kahl’s concept of action, which underlies her work “Circular Movement of Both Hands Simultaneously in One Direction and Slow Increase of the Speed of Movement” (1974) — where the lower hand, as the tempo increases, begins to move in the opposite direction — this conception appears very current and relevant, as it makes the phenomenon of cerebral asymmetry visible.

In connection with this, Margrit Kahl conducted an experiment in which she walked blindfolded across an open field for a distance of 50 meters. Her path curved to the right.

The viewer of her work “Asymmetry of the Free Movement of Man” (1971) will likewise recognize that both the asymmetry of the brain and the gravity of the Earth play a significant role.

The question, however, arises as to whether Margrit Kahl is consciously aware of these interrelations, or whether her concepts arise from intuition.

The starting point of Margrit Kahl’s artistic interest was the study of traditional sculpture, which she was already engaged in before her later teacher, Franz Erhard Walther, arrived in Hamburg.

Her main interest at that time lay in life studies, where, in drawing or sculptural studies of the human body, the aspects of statics, proportion, and space constitute the essential conditions of form.

However, since for her the central question was not the fixed representation of the human being as a sculptural figure, but rather the existential problem of human existence, she came to the conviction that she had to liberate herself from the statics of sculpture.

This first took place through the attempt to capture sequences of movement in drawing before a model, in which the factor of time played a crucial role.

Franz Erhard Walther’s definition of an expanded concept of art prompted Margrit Kahl to undertake a thorough reflection on her previous work.

It became important for her to find a form through pure movement, through its dynamic aspect, that is — without object, material, or sculpture.

The physiological conditions of movement appeared to her worth investigating; these studies at first had nothing to do with art. The artistic treatment of these phenomena, however, took place primarily on an intuitive level.

Because she works with bodily movement, there is a risk that her creative-phenomenological practice might be misunderstood as Behaviour Art.

It is noteworthy that Karl Thomas, in his “Keywords of Twentieth-Century Art,” classifies Walther’s work as Behaviour Art — erroneously equating it with Pop Art and Socialist Realism, which view the human being as an object and product of society.

To return once again to “Asymmetry of the Free Movement of Man”: one might also consider another aspect — namely, the attempt to visually represent the difference between the supposed objectivity of science and human subjectivity. Here, the human being is viewed as a subjective entity.

Margrit Kahl presents her works in series. In doing so, she deliberately avoids the possibility of any supplementary linguistic interpretation.

Most modern artists give their works only psychological and/or sociological interpretations, without taking the humanistic dimension into account.

How, then, does Margrit Kahl understand this discrepancy?

She refers to Husserl’s phenomenology. Edmund Husserl opposed psychologism and maintained that logic must be kept separate from psychology.

He regarded logic as a pure a priori science, dealing, among other things, with concepts and parts of propositions as timeless ideal entities.

Margrit Kahl considers it necessary to present her works in series, since sequences of movement always unfold within real temporal duration.

She cannot imagine an “external synthesis” of a movement, as this would contradict its very nature.

For her, literature has little in common with visual art, and she therefore insists on excluding any literary aspect.

However, she does not oppose a humanistic interpretation of her work.

Her concern is with the totality of the human being.

Such an “externally synthetic” representation of the whole would, in her view, obscure certain moments of experience.

In the visual comparison of forms, she perceives the possibility of obtaining an image of the multidimensional human being.

For her, the phenomenological comparison of forms is a way of approaching a consciousness of human totality.

It may at first seem contradictory that Margrit Kahl maintains a phenomenological and synthetic approach, yet works consistently in a structuralist manner, assuming a separation between visual art and literature.

However, this issue is not relevant for her, since she understands literature as description and visual art as the generation of form from a principle of creation.

Nevertheless, she does not exclude empathy within creative and anthropological attitudes, and in this structuralist sense, such a position does not, for her, contradict a phenomenological orientation.

Here, she returns to Husserl, who conceived synthesis as the primordial form of consciousness and identification as a basic form of synthesis.

Husserl completely distinguishes between ordinary analysis, which proceeds analytically from the “data” of consciousness — that would correspond to the structuralist view — and intentional analysis of consciousness, which also leads to divisions but whose distinctive function is the revelation of potentialities.

When Margrit Kahl engages with elementary bodily movements, she necessarily arrives at an analytical consideration of form.

Questions associated with this — of symmetry and asymmetry of the body, as well as of the Earth’s gravity — have, of course, long been known to scientists, philosophers, and artists alike.

Yet these insights have exerted upon Kahl such a powerful compulsion toward an analytical state of consciousness.

This tendency has become clearly visible in contemporary visual art since the mid-1970s — for instance, in Peter Campus, who projects his own image and double image through video.

One may ask whether this long-familiar theme of self-reflection in art history is related to self-representation in Happening and Performance Art, or to the persistently claustrophobic and schizophrenic feeling expressed in Expressionism.

The art of Margrit Kahl can be described as cerebral, since it constantly appeals to both hemispheres of the brain.

The risk exists that her work might be interpreted merely as drawing upon the insights of biology and physiology, and thereby assigned to a purely Skinnerian mode of thought. How does she distinguish between experience (Erlebnis) and understanding through experience (Erfahrung), and how has this distinction influenced her work?

When she reflects on an original experience, she presupposes a previously applied reductive method. For her, Erlebnis (lived experience) is associated with chance and spontaneity.

The asymmetry in the Yin-Yang symbols and Zen Buddhism have undoubtedly inspired her — Yin and Yang, which symbolize all the fundamental conditions of life’s dualisms: the male and the female, day and night, heaven and earth, the positive and the negative.

Margrit Kahl considers Concept Art to be sterile, because this artistic direction is based primarily on thought rather than on perception.

However, when it deals with human action, a conceptual starting point is inevitably contained within it.

She regards it as a limitation when Idea Art is intended only to generate concepts, while the element of sensory perception is missing.

For the act of action, however, she makes use of conceptions, since through them she determines movement parameters.

Because Margrit Kahl’s art can be viewed both philosophically and psychologically, it is necessary to relate her work to the newer tendencies in art as well as to the intellectual efforts to engage with questions of human existence.

It is evident that the collapse of modern society, both socialist and capitalist, signifies not only an ideological crisis but also the consequence of a certain mathematical progression — characterized, among other things, by inflation, militarization, environmental crises, overpopulation, and unemployment.

If we take as our point of departure American Abstract Expressionism, with Jackson Pollock at its forefront, or consider Pop Art, Minimal Art, Concept Art, Happening, or Performance Art — in short, all the newer tendencies that developed from the late 1950s to the mid-1970s — we can understand that, in my view, they perfectly illustrate the four pillars of materialist philosophical positions: structuralism, psychoanalysis, Marxism, and, to some extent, existentialism.

Yet the elegance of this correspondence is not without tragedy. The artist, equipped with his modern video technology, has often witnessed with his own eyes that the dream of man as a robot has no future, and that the pursuit of material enrichment encounters definite limits.

There is therefore no other way out than to create autonomy in form and/or in artistic conception.

Without denying the positive aspects of advanced industrial society, and without wishing to appear anachronistic, some artists have finally come to understand the destructive tendencies inherent in such artistic movements.

The content of Margrit Kahl’s art is of great relevance to modern humanity, for it visually represents the lack of coordination and balance in the brain caused by technology.

It is no coincidence that a number of modern artists have been dealing with the problem of the brain at a time when mini-computers are already in the hands of schoolchildren.

That artists such as Seurat, Malevich, Mondrian, Yves Klein, and Ad Reinhardt — to name only a few — have represented, through their paintings and imagination, Newton’s theory of color in a behaviorist–metaphysical way within twentieth-century art, already points clearly in this direction.

The question arises whether an exclusively behaviorist art, such as Pop Art and Socialist Realism, might not lead to a far-reaching degradation of the human being.

The creative-phenomenological intention that Margrit Kahl pursues in an extremely structuralist world is directed toward achieving a greater human equilibrium.

Jean Sellem

(*) Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media, Preface, pp. 7–9, Collection Points, Paris 1977.